READ BY CHAPTER

Being the Change: Live Well and Spark a Climate Revolution

11. Meditation, a Foundation of Change

We don’t do siting meditation in order to become a Buddha. We sit to be happy.

— Thich Nhat Hanh

Whereas the immediate physical cause of global warming is our greenhouse gas emissions, the deepest underlying cause of the broader predicament is our wanting. Wanting drives both consumerism and overpopulation. We endlessly want more: more money, more sex, more prestige, a faster car, a bigger house, fancier furniture. And when we get something we want, the relief from our desire is fleeting. In a short time, we again want more. Wanting is a bottomless pit.

Not only is our wanting straining the biosphere to its breaking point, it’s causing us to suffer. When we want something, it’s because we’re not satisfied in the present moment. Indeed, the entire purpose of the advertising industry is to cause us to feel unsatisfied with what we have. When we want, we feel agitated, unable to appreciate the miracles right in front of us.

This dissatisfaction is suffering, but we may be so habituated to it that we don’t recognize it. In this chapter, we’ll discuss a simple practice that allows us to escape our wanting: meditation.

Meditation is a practice, not a religion. Remarkably, it requires no mystical revelation, no blind faith, no spiritual conversion. You become your own teacher. You learn by observing yourself in a straightforward way.

Many activists feel that siting in stillness is a waste of time, but this isn’t my experience at all. On the contrary, meditation makes my actions more effective by making them less full of ego. Meditation also bridges the disconnect I mentioned in Chapter 1, the gulf between what we know to be right and what we actually do. The intellect isn’t capable of crossing this bridge. For these reasons, daily meditation is the foundation of my personal response to our predicament. It allows me to become happier, even as I carry a deepening awareness of the unnecessary suffering we’re inflicting upon the biosphere, and ourselves.

The mind’s basic habit

It’s incredible that most of us go about our daily lives without ever stopping to observe our minds— how they work, and how suffering and happiness work. Most of us remain ignorant about our own minds, from birth to death.

Once you start observing it, you’ll quickly notice that the mind is constantly reacting to pleasant and painful sensations in the body, even in sleep. Every fidget, for example, is a response to a sensation somewhere. When there’s a pleasant sensation, the mind wants it to continue. When there’s an unpleasant sensation, the mind wants it to stop. This is the mind’s basic habit.

This subconscious habit, in turn, causes negativities like anxiety, jealousy, anger, hatred, and depression. For example, when we’re anxious, it’s because we’re afraid of future unpleasant sensations, or of missing out on pleasant sensations. When we’re angry, it’s because we think someone or something is preventing pleasant sensations or causing unpleasant sensations.

It’s impossible to deal with these negativities through willpower alone. I can’t consciously will myself never to get angry, because anger is an instinctive, subconscious reaction that takes me by surprise and overpowers my conscious will. Instead, I need a practice capable of changing my mind’s basic habit.

Our natural tendency is to try to run from sufering by constantly seeking pleasant sensations, without realizing that doing so only reinforces the mind’s habit. We try drinking, drugs, sex, money, work, TV, getting on airplanes— all to no avail. Because every sensation, no matter how pleasant, sooner or later passes away. Our society is built around chasing happiness through consumption. But lasting happiness can never be found in this way.

We can’t escape our minds. They follow us wherever we go. A more practical option is to make them good places to be.

Stillness and silence

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of meditation, let’s take a moment to consider stillness. People in our society are always running, anxiously putting out fires in their lives. They keep running, mentally if not physically, right up to their last breath. But without stillness, it’s impossible to know who we are and what we want out of life. If we don’t know these things, we’re just running pointlessly.

Since we’re always running like this, when we do get an opportunity to sit in stillness, it’s disconcerting. We want to get up and start running again. The stillness can be frightening to us, because when we’re still, we may come face-to-face with our suffering. Being still, at first, is like riding a bucking bronco. But to come out of the suffering, we need to face it; and to face it, we need to be still.

Stillness takes courage

Our constant running is tied, bidirectionally, to our fossil fuel addiction: fossil fuel makes us run ever faster, and our running makes us love fossil fuel. We run noisily. We surround ourselves with television, even in public places. We put earbuds in our ears.

The sound of cars and freeways is everywhere. In our houses, even when we think it’s quiet, the refrigerator will switch on.

I long for quiet places, but they’ve become difficult to find. I’ll put on a backpack and walk in the backcountry for days, only to hear a nearly continuous roar of airplanes overhead. I seek out quiet, because to me it’s as beautiful as the night sky in the darkest mountain wilderness. This beauty is part of the vision I hold for a world without fossil fuels.

The practice

There are many ways to meditate. Here, I’ll explain the simple and concrete technique that I practice, but this is not a meditation lesson. It’s merely a description. I know that I couldn’t have established my practice at home from a written description.

If you want to learn, it’s best to go to a meditation center.1 Although the practice is simple, the mind is a slippery fish. It will strongly resist your attempts to change its deepest habit. The mind will think of surprisingly creative and persuasive excuses to stop siting and get up.

To learn meditation, you need a firm commitment, a quiet place free from responsibilities, a sustained, single-minded persistence over at least ten days, and a teacher who can answer any questions that come up.

How Sharon and I became meditators

My upbringing, as a not-so-devout Roman Catholic in the suburbs of Chicago, was about as far from the mystical East as it’s possible to get. But in college, I discovered Indian music and seriously considered becoming an ethnomusicologist. After college, while teaching high school physics and astronomy in rural southeast Massachussets, a musical friend from India called me to say he was attending something called a “vipassana course” a few hours away. The logistics for meeting up didn’t work out, though, and I didn’t follow up on the vipassana thing.

A few years later, while having brunch at the Cornelia Street Café in Manhattan, another friend casually mentioned that she was going to serve at a meditation course for ten days. She’d be cooking food for the meditators and doing their dishes. Intrigued this time, I found an essay entitled “The Art of Living”2 which resonated strongly with me; the basic idea was that we’re suffering, but through direct observation (which I’d never thought to do), we can figure out the cause of our suffering and how to eradicate it.

Sharon was also at that fateful brunch. During her time in the Peace Corps (while I was teaching high school), she’d read Robert Turman’s Essential Tibetan Buddhism3 along with other Buddhist texts, and tried to teach herself meditation. However, she found learning meditation from books to be impossible. She was also eager to try vipassana.

So we signed up for the next available course, headed to the Port Authority bus terminal, and hopped a Greyhound to Shelburne Falls, Massachussets. Over the ten days, we’d live segregated by sex; we agreed that if either of us thought we’d stumbled into a cult, we’d sneak across to the other side and we’d leave together.

But as the course progressed, I grew more and more convinced that this was the real deal. During the course, I experienced the highest highs and the lowest lows— and had my first taste of equanimity. I was forever changed, and so was Sharon.

Experiencing change

You can always follow your breath. Observe the flow of air through your nostrils with each inhale and exhale. Notice the slight tickle on your upper lip, the warm or cool fow of the air. Witness these subtle sensations as you breathe naturally. As long as you’re living, your breath will be there for you— in any situation. Working to follow the breath, for longer and longer periods, sharpens the mind and prepares it for the core practice of meditation.

This core practice is an extension of the breath awareness: to observe the normal, everyday sensations throughout the body (pain, moisture, heat, tingling, etc.) without reacting to them. The goal is to observe and do nothing— to break the habit of reaction.

In life unwanted things happen and wanted things don’t happen. We can’t control this. But we can learn to dampen our reaction. Toddlers, and even most adults, immediately react with a tantrum. They suffer immensely and cause everyone else to suffer as well. A meditator, though, will smile calmly— because this too shall pass— and then, with a clear mind, get on with the work of making a better world.

Being quietly aware of the sensations on my body, I see that they come and go on their own. They’re constantly changing.

Experiencing this impermanence, I develop equanimity. What’s the point of being attached to this or that sensation, when sensations are impermanent? Why multiply my suffering through such meaningless attachment? Direct, sustained experience of impermanence gradually breaks the habit.

As best I can, I remain alertly aware as I patiently scan up and down, from the top of my head to the tips of my toes and back, examining every area of my body as I pass it. Suppose that in this

moment, my attention is on my right shoulder. I quietly observe whatever sensation my right shoulder is experiencing. It doesn’t matter whether it’s pleasant, painful, or neutral. It always arises, and then passes away— impermanent. Then I move to my right upper arm, and repeat. Ten to my right elbow, and so on, covering the entire body systematically. If my mind wanders away from this exercise, which it often does, I bring it back without disappointment or frustration. This, too, is part of the practice.

Every sensation is a tool for coming out of the habit of blind reaction. Observing pleasant sensations without reacting dissolves negativities associated with greed. Observing painful sensations without reacting dissolves negativities associated with hatred. And observing neutral sensations without reacting dissolves negativities associated with boredom.

By directly observing bodily sensations, I experience that they are impersonal, and that attachment to them (projecting “me” into them) causes suffering. As I sit still, sensations come and go on their own. By experiencing their changing nature, I experience the changing nature of this mind-body composite I call “me.” Experiencing it, I realize that I’m impermanent. The notion of “I” gradually dissolves.

The ego is like grime on a window. Once the window is washed clean, the underlying reality of connection shines through like the sun.

Other aspects of the practice

This practice— the equanimous observation of change, in the framework of bodily sensations— is called vipassana, which means “seeing things as they really are.” It’s the practice Gotama (the Buddha) discovered and used to come out of his own suffering.

There’s nothing religious about the practice. Buddha wasn’t interested in creating sects labeled “Buddhist.” He simply taught people a practice he’d discovered that allowed him to come out of suffering.

Buddha taught two other helpful practices. The first is breath awareness, anapana (which means inhalation-exhalation). The second is wishing all beings to be happy, a meditation of sharing peace, meta bhavana (which means cultivation of loving kindness).

About once a year, I go on a ten-day meditation course. The first three days are devoted to anapana. The mind is naturally wild and unstable, wandering randomly from thought to thought, wallowing pointlessly in regrets of the past or anxieties over the future.

Practicing breath-awareness gradually tames and sharpens this wild mind, preparing it to practice vipassana more effectively.

At home I meditate for an hour after waking up and an hour before going to sleep. After these sits, I practice meta meditation for a few minutes. I remain aware of sensations while wishing other beings to be happy. If there’s anyone for whom I’ve felt ill will, I might direct my meta to that person. I put myself in that person’s situation, understand his or her hopes and suffering. As I’m practicing this, I’m aware that others are also practicing it. For me, the realization that there are other beings selflessly wishing for everyone to be happy and peaceful is a great source of strength. There is help, and love, and goodwill out there.

To support the overall practice, it’s important to avoid killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct, and intoxicants. These things both arise from and encourage reacting blindly to craving or aversion, reinforcing the mind’s basic habit and causing harm to oneself and to others.4 They also agitate the mind, as I know well from my own experience. As I continue to practice vipassana, avoiding these harmful actions becomes easier. This isn’t puritanism: there’s no repressed desire. Instead, I simply experience that when I break these precepts, I suffer. So I prefer not to break them. The desire evaporates.5

Mindfulness is the capacity to remain aware of what’s actually happening, within and without. As I continue practicing, the distinction between siting meditation and other times is becoming less sharp. I try to maintain awareness of some bodily sensation or breath at all times I’m awake. Although I don’t succeed at this yet, it helps me to remain mindfully in the present moment, whether or not I’m siting in meditation.

Some benefits of vipassana

Although meditation teaches us to come out of craving, it’s important to experience tangible benefits. Otherwise there’s no way you could sustain siting for two hours every day! I personally find that spending two hours per day is absolutely worthwhile. Indeed, if you’re getting no benefit from your practice, it’s a sign that you might be practicing incorrectly; in this case it can help to talk to a teacher.

What are some benefits? First, the stress and anxiety in my life evaporates. I’m less concerned with outcomes. If I let my practice slip, shortening and skipping some of my daily sits, anxiety creeps back into my life. When I start practicing steadily again, the anxiety goes away. My work is just as challenging while I’m meditating, but I’m able to see it for what it is: not me. With a detached mind, I work more effectively and make better decisions.

Second, I become unconcerned about what others think of me. As a nerd growing up, I desperately wanted to be seen as cool. Even as an adult, I craved that people would think about me in a positive way. This was mental slavery: when I felt someone thought well of me, I’d feel happy; when I felt someone thought ill of me, I’d feel unhappy. Now I simply do what I need to do.

Third, I suffer less from all types of negativity. I have less anger, less depressed feelings, less loneliness, less hatred, less craving for extramarital sex, less jealousy, less negative self-talk, and less impatience. This means less suffering for me. It also allows me to have more harmonious and satisfying relationships with my family and friends. Sharon and I fight far less, and far less intensely, than we used to. I hate no one, and I see how all my past hatreds originated in myself. Everyone is my friend. Even the thought that someone could be my enemy seems odd to me now.

Fourth, I feel more gratitude and connection. I see how precious life is. I feel more gratitude for the people in my life. I fight with them less, and it’s easier to give them meta. More compassion and openness allows me to connect easily with strangers. People come up and talk to me. I smile, they smile.

You may or may not experience these benefits, and you may experience others. Take care not to crave some specific benefit, however, as this will reinforce your mind’s habit of wanting. Just let your practice unfold over the years. You can’t predict how this will happen.

Keep in mind, though, that there’s only one measure of progress in this practice: equanimity. If you practice correctly, you will become more equanimous. This will necessarily make your relationships with others more harmonious. If you don’t feel more equanimity and harmony with those close to you, you need to make some correction.

Meditation and the brain

Meditation feels like a fundamental rewiring of the brain. From a neurological perspective, this turns out to be the case. Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to learn by changing its structure, rewiring itself as we learn a new skill, such as a sport, a musical instrument, a language— or meditation. I think it’s interesting to take a detour and see what science has to say about meditation.

My goals in so doing are to present meditation from a complementary perspective, and also to allay any fears you may have that meditation is some mystical or religious thing. It’s just a practice.

An incredibly valuable practice, but still just a practice.

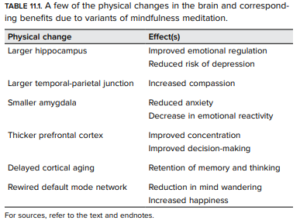

Above I provide a brief summary of a few (though by no means all) ways the brain changes due to meditation (summarized in Table 11.1). I’ve chosen studies focusing on mindfulness meditation, a generic term signifying meditation that is similar to vipassana (i.e., equanimous awareness of bodily sensations).6

Significant regional changes in gray mater volume and density occur after as little as eight weeks of 30-minute per day meditation practice.7 Meditators show significant increases in the left hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with emotional regulation, learning, and memory.8 Conversely, people with major depression have a smaller hippocampus.9 These two facts, taken together, suggest that meditation prevents depression— a hypothesis which other studies10 (and indeed my own experiences11) confirm.

The right temporal-parietal junction (a brain region above the

right ear), which is associated with empathy, compassion, and self-awareness, grows larger.12 Te amygdala, associated with anxiety and the fight-or-fight response and known as the “fear center,” shows a reduction in gray mater due to meditation, and decreases in gray mater there have been correlated with decreases in stress.13

Cortisol, the stress hormone, is decreased after a period of meditation.14 Finally, the prefrontal cortex, associated with higher order brain functions such as awareness, concentration, and decision making, becomes thicker with meditation.15 The cortex usually shrinks as we age, which is why as we get older we experience memory loss and difficulty in thinking; but meditators didn’t show the usual decrease in cortical thickness with age, implying that meditation prevents the brain’s usual atrophying with age.16 And there’s evidence that meditation prevents age-related cognitive decline.17

Meditation also affects the brain’s “default mode network,” the neurological wiring responsible for the default behavior of our minds, which is to wander.18 Other studies have shown that a wandering mind is correlated with unhappiness.19 The main nodes of the default mode network are less active in meditators, both while meditating and while not meditating (in other words, the changes persist in daily life). A new network becomes active instead, coupling parts of the brain associated with self-monitoring and cognitive control (the posterior cingulate, dorsal anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices).20

Researchers have also demonstrated that meditation reduces pain,21 cures insomnia,22 boosts the immune system,23 and lowers blood pressure.24

A universal path that isn’t for everyone

While anyone can practice vipassana, not everyone will feel drawn to it. Many people simply aren’t seeking to change themselves, to come out of their suffering and live a more harmonious life. Other people are seekers who are drawn to different paths. Other practices that lead people to actually increase their equanimity, compassion, and happiness are also good practices.

If the practice increases your ability to respond to the negativity of others with compassionate love, and your relationships with others grow more harmonious, then the practice is helpful.

Meditation and our predicament

Vipassana meditation is a fundamental part of my response to living in a warming and overpopulated world undergoing rapid transformation. As part of my daily work, I look directly at the truth of global warming, and what it’s doing to the inhabitants of the Earth.

Meditation gives me the strength and the courage to keep interacting with this truth, as it is— not only to cope, but to be happy and as effective as possible in enacting positive change.

Meditation drives my ability to change myself. Because of meditation, my desire to consume has greatly diminished. I no longer have any desire whatsoever for vacation homes, sports cars, or private jets. I’m happy with enough.

By experiencing connection, the last thing I want is to intentionally harm other beings. By experiencing how all actions have effects, I wish to perform only actions that are good for me, good for others, and good for the biosphere.

Meditation has been, and continues to be, the key to aligning my actions with my principles.

The ability to see reality as it is (and not how I want it to be) leads to acceptance of my situation, which leads to appropriate action. When we’re in danger, we need to recognize the danger correctly before we can act in our best interest. If we delude ourselves, denying the existence of the danger, having false hopes, or perceiving the situation through the lens of a preexisting mindset, we’ll act accordingly.

Meditation develops gratitude, something that’s critically lacking in industrial society. When I view food, water, energy, community, and time as precious things I’m grateful for, I actively seek ways to avoid waste. This becomes a joyful task.

Meditation also develops compassion.

This is particularly relevant to our predicament: if we feel hatred toward the oil company executives and the ultra-rich, for example, we are still planting seeds of hatred. If we manage to change the social regime, but we do so through violence, greed, and ignorance, only more violence, greed, and ignorance will grow out of our actions. History will continue to repeat.

Finally, meditation reduces conflict and makes living in community much easier. As global warming intensifies, and global systems break down, we’ll increasingly turn to our communities.

By allowing us to observe and temper our automatic responses, meditation facilitates discussion across ideological divides, which is more important than ever. The ability to interact with others, free from the destructive narcissism of the human ego, is as helpful to the members of a family as it is to heads of state.

The experience of real happiness and love is there for each of us all the time, underneath, but it gets clobbered by the intensity of the noise of “me,” the noise of fear, anger, selfishness, jealousy, hatred, regret, hopelessness, and wanting. It’s impossible to truly love with all that noise. We’ll come out of the nightmare of history only after enough of us learn how to generate love for all beings.

The sages have been saying “love one another” through the ages. But without a practice, a simple technique that works, these too easily become empty words. In vipassana, we have just such a simple, concrete practice, available to all, that allows us to actually come out of selfishness and hatred, that allows us to come out of this illusion of “me.” What a wonderful thing!

As I directly experience the constantly changing nature of my body and mind, my ego gradually dissolves. As my ego dissolves, my experience of connection deepens. I experience that there’s no “me,” only a flow. I experience that I’m a form that arose out of these quarks and leptons, these subatomic particles which physicists believe are themselves ultimately just vibrations. This form will come apart again. Like you, I’m a fold in the universe that took this human shape for some time and will change, like foam on the surface of the ocean. What once seemed solid and permanent was actually a flow dependent on the food we eat, the existence of our parents, the existence of the biosphere, the existence of stars.

And then, when the illusion of separation dissolves, what’s left is love. A love without attachment, arising from a tiny conscious piece of the universe. A selfless love that positively radiates kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity.

- In the vipassana tradition, there’s no charge for courses, which run on a “pay it forward” basis through donations from people who have taken at least one course. Te teachers and the people who run the course and cook the food are volunteers. This commitment to noncommercialism and selflessly helping others maintains the purity of the teaching. For more information: dhamma.org.

- S.N. Goenka. “Te Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation.” [online].

dhamma.org/en-US/about/art. - Robert A.F. Turman. Essential Tibetan Buddhism, rev. ed. HarperOne, 1996.

- Taking intoxicants may seem relatively harmless. However, being intoxicated makes it easier to break the other four precepts. For example, drinking makes it much easier to act violently. Also, I have friends who’ve received drunk driving convictions, which caused them great suffering.

- For me, the transition away from breaking these precepts was gradual. For example, early in my meditation practice, I drank alcohol every day. As I practiced, I became aware that alcohol gave me a feeling of mental cloudiness and sapped my energy. I preferred feeling sober, so I gradually started drinking less. I’ve become sensitive to the distinct taste and smell of alcohol, and I don’t like it. If you love beer and wine, as I did, you don’t have to be afraid to give them up. But when you do drink, you will probably have a heightened awareness of the

associated sensations, and you might choose to drink less. - There are studies based on other meditative techniques which also demonstrate benefits. There are few head-to-head studies comparing different meditation techniques.

- Brita K. Hölzel et al. “Mindfulness practice leads to increases in

regional brain gray mater density.” Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 191 (2011). [online]. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006; Sarah W. Lazar et al. “Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness.” Neuroreport 16 (2005). [online]. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc /articles/PMC1361002/. - Hölzel et al. “Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray mater density.”

- Yvete I. Sheline et al. “Depression Duration But Not Age Predicts Hippocampal Volume Loss in Medically Healthy Women with Recurrent Major Depression.” Te Journal of Neuroscience 19 (1999). [online]. jneurosci.org/content/19/12/5034.full.

- For example: Zindel V. Segal et al. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Terapy for Depression, 2nd ed. Guilford Press, 2012.

- While in my early twenties, I had a bout of severe depression. I cannot begin to express the awfulness of that experience; I’m grateful to have made it out alive. Twice since I began meditating in 2003, during periods of stress during which I wasn’t keeping my regular meditation, I felt a sort of mental pain or pressure that reminded me of being depressed. It felt as though depression were trying to find its way back in. Both times, simply reinstating my meditation routine caused that feeling to vanish after a day or two. What’s more, my meditation experience is what allowed me to quickly recognize the incipient mental sensation in the first place.

- Hölzel et al. “Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray mater density.”

- Philippe R. Goldin and James J. Gross. “Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder.” Emotion 10(1) (2010). [online]. doi:10.1037/a0018441.

- T.L. Jacobs et al. “Self-reported mindfulness and cortisol during a Shamatha meditation retreat.” Health Psychology 32 (10) (2013).

[online]. doi:10.1037/a0031362. - Lazar et al. “Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness.”

- Ibid.

- T. Gard et al. “Te potential efects of meditation on age-related cognitive decline: A systematic review.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1307 (2014). [online]. doi:10.1111/nyas.12348.

- Judson A. Brewer et al. “Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity.”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (2011). [online].

doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108. - Mathew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert. “A wandering mind is an unhappy mind.” Science 330 (2010). [online]. doi:10.1126/science.1192439.

- Brewer et al. “Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity.”

- N.E. Morone et al. “Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study.” Pain 134(3) (2008). [online]. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.038.

- David S. Black et al. “Mindfulness Meditation and Improvement in

Sleep Quality and Daytime Impairment Among Older Adults With Sleep Disturbances: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine 175 (2015). [online]. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8081. Also, vipassana cured my

mom’s persistent insomnia.